Abolishing Performance Appraisals (An unprofitable Conversation)

Performance appraisals have been referred to by Stephen Covey, the renowned author of “The 7 Habits of Highly Successful People”, as the bloodletting of today’s management.

More than a dozen other leading business authors, scholars and consultants, including Peter Block, Philip Crosby and W. Edwards Deming, have also condemned and discouraged the use of performance appraisals.

Why?

I first came across the book “Abolishing Performance Appraisals: Why they backfire and what to do instead” by Tom Coens and Mary Jenkins some eight or ten years ago, when the title jumped out at me in a book shop.

Coens and Jenkins don’t’ mince words; they hate performance appraisals and see very few redeeming features in them. While they acknowledge the noble intent behind performance appraisals, they believe they don’t work, never have and are, often, counter-productive to the organisation’s goals. They point out that performance appraisals are a by-product of a management philosophy – management by objectives (MBO) – that emerged in the 1950’s. Despite this machine model of human behaviour being discredited in the 1980’s and finally dying out in the 1990’s performance appraisals persist today, as an undesirable legacy of that era.

Coens and Jenkins define a performance appraisal as “…a mandated process in which, for a period of time, all or a group of employees’ work performance, behaviours, or traits are individually rated, judged or described by a person other than the rated employee and the results are kept by the organisation.” They go onto point out that while performance appraisals may go under many names, e.g. annual review, performance review, performance evaluation etc., if they fit the definition the impact is the same.

Some organisations indicate they have re-designed their appraisal system to address the perceived deficiencies. Coens and Jenkins argue that the problem is not in the design but in the inherent nature of the performance appraisal, itself. Performance appraisals start with the wrong view of people: “Instead of motivating people, they reduce them to dependent, de-motivated people, who are treated as though they need to be prodded and psyched to put forth their best efforts.” In short, they treat adults as children.

Since reading that original book I have come across many other similar articles supporting the arguments of Coens & Jenkins. In March 2019 Harvard Business Review published an article titled “The Feedback Fallacy” by Marcus Buckingham and Ashley Goodall.

Their research identifies three key reasons why employee performance evaluation and ‘constructive criticism’ doesn’t work:

Human beings are unreliable raters of the performance of others. Our personal biases impact at least 50% to 60% of our assessment. And no amount of training seems to diminish the level of this bias. Also, because bias is a systemic error, rather than a random error, no amount of averaging of the raters scores increases its accuracy. Often the reverse occurs. The authors point out that it does not matter how many blind people you ask about the colour of something. Averaging their answers does not make the result any more accurate. This is because blindness, like bias, is a systemic error.

Criticism inhibits the brain’s ability to learn. It uses the same neural pathways as ‘fight or flight’. So instead of learning people often recoil and defend against the criticism. Learning actually shuts down. The authors point out that taking people too far out of their comfort zone inhibits learning.

Excellence is an outcome and not a prescribed well-trodden uniform path. The path to excellence is idiosyncratic and therefore is dependent not only on the context but also on the uniqueness of the individual. You don’t need to look very far to see that this is true. Look at all the lauded leaders throughout history then look at how idiosyncratic their approaches are.

To get to excellence you need to be building on the strengths of the individual and not trying to correct their perceived ‘deficiencies’. Correcting deficiencies, as Buckingham and Goodall clearly point out, at best, only helps prevent failure. And preventing failure does not lead to excellence.

In short, Performance Appraisals are a prime example of unprofitable conversations, from a by-gone era, that can actually damage performance.

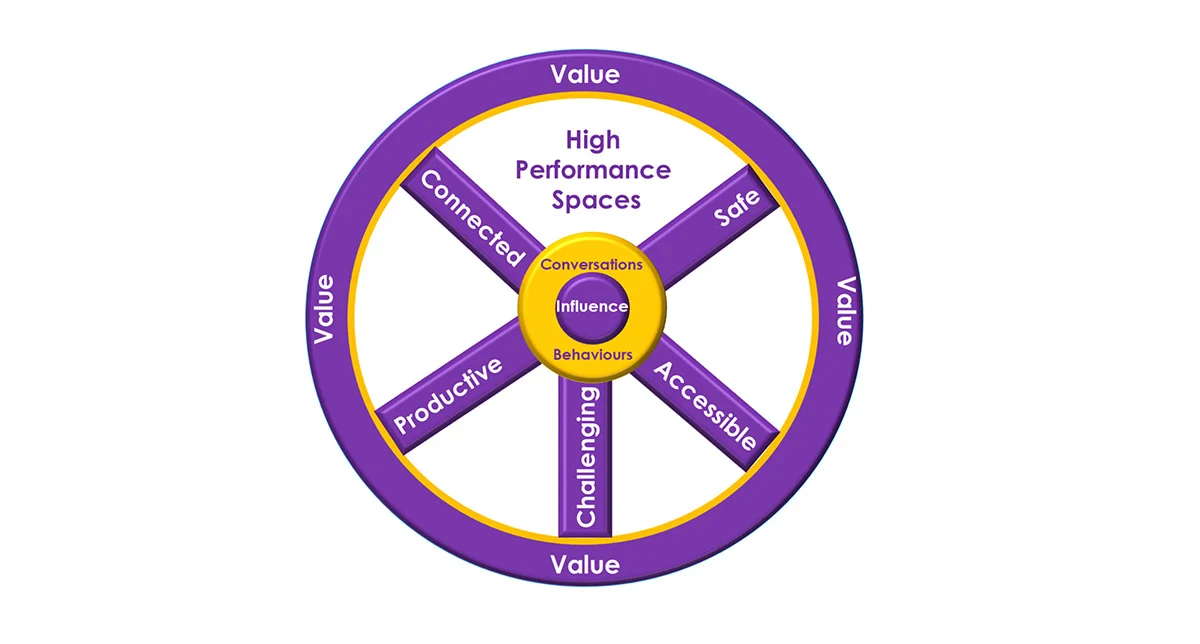

Next month I will explore some of the suggested (‘Profitable Conversation’) alternatives to building high-performing resilient people.

Warwick Cavell is a thought leader in communicating for results and strategy implementation. For over 25 years, he has helped leaders improve business performance by changing the way people communicate and work to solve problems – both internally and with their clients. He is a highly respected facilitator, coach, speaker and trainer, and author of regular blogs.